Business, Politics, and Beavers

Lewis Henry Morgan pursued the scholarship for which he is known today as a sideline to his work as a corporate lawyer. Early in his career he participated in both the booming commercial life of 19th-century Rochester and the viciously partisan politics of the era. With the support of a sizeable fortune amassed through his investments in railroads and iron mining, Morgan dedicated the last years of his life entirely to his research and writing.

Elected Representative

Morgan’s training as a lawyer and admission to the bar in 1842 prepared him for elected political office. His career in the New York State Legislature began when he served in the State Assembly for a single term in 1861. In a letter written that year to William Henry Seward, Morgan admitted to having been “a lazy Republican,” but one who had “always felt a lively interest in the success of the principles of the Republican Party.” His political opponents were often less kind. Morgan later served a single term (1868-1869) in the State Senate in which his father, Jedidiah Morgan, had served from 1824 to 1826.

In League of the Iroquois (1851), Morgan decried the attempt made by the Ogden Land Company to dispossess the Tonawanda Senecas of their remaining land in New York State.

“It is no small crime against humanity to seize the fireside and the property of a whole community, without an equivalent and against their will; and then to drive them, beggared and outraged, into a wild and inhospitable wilderness. And yet this is the exact scheme of the Ogden Land Company…”

Morgan sporadically engaged in public advocacy for the interests of Native Americans over the course of his life. As a young man, he supported the Tonawanda Senecas in their struggle against the Ogden Land Company. While in the State Assembly, Morgan chaired the Committee on Indian Affairs. His later advocacy, although informed by assimilationist assumptions, took the form of protesting U.S. government policy toward Native Americans in letters to presidents Abraham Lincoln and Rutherford Hayes and in critical commentaries published in The Nation.

Smart Investor

Hervey Ely’s Mills, On the East Bank, 1838. Reproduced from a wood engraving by John H. Hall in Henry O’Reilly, Sketches of Rochester (1838).

Morgan shrewdly invested the money he earned from his law practice with George Danforth in the business ventures of Samuel P. Ely and George H. Ely, brothers who owned several Rochester flour mills. The Elys were later attracted to the growing iron mining industry in the West. The Upper Peninsula of Michigan proved to be a lucrative site for railroad interests because transportation was needed to move iron ore from the mines to a port on Lake Superior. Morgan invested in and served as a lawyer for the Bay de Noquet and Marquette Railroad Company. This experience later helped him when he served on a New York State Senate standing committee reviewing railroad legislation. Morgan also helped form the eponymous Morgan Iron Company. The business’s innovative blast furnace produced pig iron that was sold very profitably during the Civil War.

Careful Observer

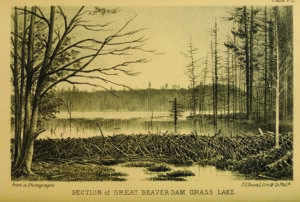

Section of Great Beaver Dam, Grass Lake. Reproduced as an engraving from a photograph by P. S. Duval, Son & Company. From Lewis Henry Morgan, The American Beaver and His Works (1868)

Morgan’s business interests required him to travel. Beavers caught his attention during his visits to Marquette, Michigan. The area was still densely forested and Morgan was impressed with the beavers’ industrious architecture–their dams, lodges, and canals. The journals of his trips to Michigan are filled with more notes about beavers than about the business purpose at hand. Morgan eventually compiled these observations into a book called The American Beaver and His Works (1868), in which he admires the animals and strives to understand them in the same way that a modern anthropologist would study an unfamiliar group of people. Morgan clearly was fond of his subjects, whom he memorably preferred to call “mutes” rather than brutes.